Emile Zola was born on this day, April 2, 1840. The French writer who is known for his famous headline J’ACCUSE in defense of Alfred Dreyfus but did you know he was also a marketing genius. It was Zola who while working for Librairie Hachette in 1862 where he spent his days packing books, until one day they recognized a hidden talent. He told them they should paint signs to sit outside the doors of shops that people would see as they walked by, and with that the sandwich board was born.

There are so many tales that can be told of Zola but this one I have been waiting months to share. Inside the Musée d’Orsay off of the main lower gallery in a small room are a few of Manet’s most amazing pieces. In 1865 when Manet presented his painting Olympia to the jury it did not go over well. They hated it, they hated what she represented and how she was positionioned and rejected it from the Salon. However one day, the young writer Emile Zola heard about the painting and wanted to see it. A friend of Cézanne, he was already a great fan of the arts and the artists. He thought Olympia was a masterpiece by an artist that was a master of the future, deserving to hang in the Louvre.

Zola did what he did best and took pen to paper. At the time he was enthralled with what was happening in Paris with the artists that were being turned away from the hallowed Salon and being forced to build their own exhibition. He wrote a pamphlet in defense of Manet titled “La Revue du XXe Siecle”. He would write another one the next year when Manet went out on his own to set up his very own exhibit during the Universal Exposition that many other artists mocked him for.

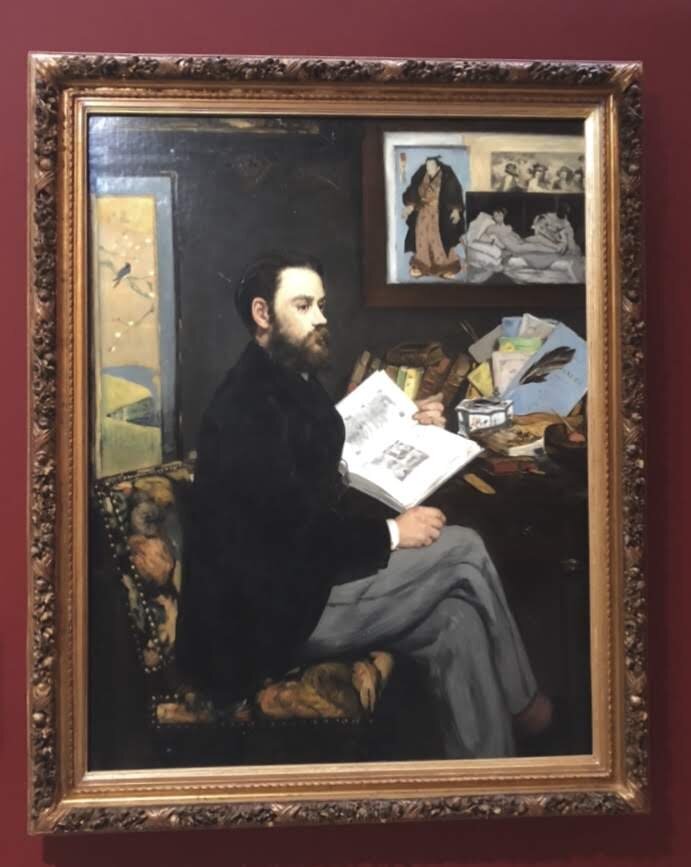

In a way of thanking his new friend, Manet offered to paint him. He invited him to his studio on Rue Guyot in 1868. Manet set the scene on the desk with elements of Zola's personality and himself. You can see the blue pamphlet that started their friendship on his desk while the quill and inkwell remind us of Zola’s life as a writer.

Zola is reading “L’Histoire des Peintres” by Charles Blanc, a book both men loved. Although, it is what hangs above the desk that makes me love this painting so much. The print of the Japanese wrestler by Utagawa Kuniaki II suggesting the influence the Japanese woodblock paintings had on the art style at the time. The screen behind Zola is another nod to the influence of the East on the artists.

To the left of that is an engraving by Velazquez of Bacchus hints at their shared love for Spanish art peaks out from the top of Olympia.

I have a fascination anytime there is a painting within a painting. So many questions come to mind, why is it there, what does it mean to the artist and what are they trying to tell us. For this one, it is quite simple. Olympia represents not only the way the two men met and a painting Zola loved, but it was also Manet’s way of righting the wrong of the Salon of 1865.

Adding Olympia into the painting of the man that in a way legitimized her meant so much to Manet. He made one small adjustment in this version, he changed the direction of her eyes away from the viewer and onto Zola himself.

In May of 1868, he entered the painting of Zola into the Salon. This time they welcomed it with open arms. Was it Manet’s work or was it that they were more afraid of what the pen of Zola would say about them? Hanging in room M of the 1868 Salon there was Zola high up on the wall, but even more so, there was Olympia hanging above the same people that rejected her so vehemently just a few years before.

The painting remained in the personal collection of Emile Zola, hanging in his home until 1925, twenty three years after his death, when his wife Alexandrine left it in her will to the Musée du Louvre. It would hang in the Louvre until 1986 and then move over to the newly opened Musée d’Orsay.

And in the end Zola was correct, Manet was an artist that would become a master and hang in the Louvre.