For years, a group of charities came together, known as the Bazaar de la Charité. Attracting the elites of society, many of which were women, would end in disaster in 1897.

Henri Blount, the wealthy son of Edward Charles Blount a former member of Parliament and banker who later invested in the railway which brought them a fortune. Along with Baron de Mackau, son of the Minister of the Navy-owned land around Paris that he would donate for the use of the fateful charity event in 1897.

The first Bazar was held from 1885 to 1887 on the Rue du Faubourg Saint Honorè. In 1888 and 1890 to 1896 on the Rue de la Boétie and in 1889 at the Place Vendome. On March 20, 1897, Baron Armand de Mackau gave a 263 feet long pine structure on the Rue Jean-Goujon in the 8th arrondissement.

On April 6, 1897 leaders of the charities included the Duchesses of Alençon & Bavaria, and Henriette of Belgium, niece of King Leopold II, and the Duchess of Uzés. Gathering 22 charities the inside of the structure was created with a large central area surrounded by smaller counters for each organization most of which were run by women. Each booth was large enough to hold a dozen ladies

The 1897 event was going to include the new technology of a Cinematograph by Auguste and Louis Lumière. The first film, 50 seconds in length, debuted on March 22, 1885, but was not seen by the public until December before the brothers took their movies on tour around Europe, New York, London, and Beaunos Aries causing an international sensation.

Three very short films were shorn on repeat including La Sortie de l’Usine Lumiere de Lyon, L’Arrivée d’un Train et la Ciotat Gare, and L’Arrouser Arrosé.

On May 3, 1897, the Bazaar de la Charitiés opened its doors. At 4 pm Monseigneor Eugenio Ciari blessed the event and 1600 people flooded into the space. The first day was crowded but the attendees were having a lovely time enjoying the fun, games, and movie.

On May 4, 1897, 1200 people mostly women and a few men and children filled the event.

When the projector was installed it was placed in a small room with little ventilation. This was the 19th century and the 35 mm projectors were far more primitive and needed ether to operate the Molteni lamp and burned through it rather quickly. After an hour it needed to be refilled. Surrounding the camera were curtains and were instructed to leave them closed. In the dark M. Bellac asked for some light to pour the ether. At 4:15 pm Grégoire Bagrachow used a match to give Bellac a bit of light. As soon as the match was lit, the vapers caught fire and ignited the canvas curtains.

Moments later the Duchess d’Alencon began to cough and could smell smoke in the air. The pine structure with canvas walls and thin wooden tables was a tinder box that burned quickly. Small explosions were heard as the gas lights ignited. Within 12 minutes the entire structure was engulfed in flames.

There were only two doors leading to the street and women and children were crawling over each other trying to exit. The few men that were there were reported later by eyewitnesses to have pushed women aside in a panic to exit. When the pompiers arrived, 425 in total there was little they could do as the entrances were jammed with people including those that died before they made it out the door.

This was 1897 when the style of clothing included hoops, petticoats, and endless ruffles all very easy to ignite and engulf a victim in flames. Out the back side of the building, a few small windows led to a courtyard. Women were crawling out the back window where a cook from the Hotel du Palais assisted in pulling 150 victims through the kitchen windows while the screams were heard. Over the next hour, brave souls tried to enter the building to save people but the swift fire was no match.

The Duchess d’Alencon, one of the event's main organizers and married to the grandson of Louis-Philippe former king of France, remained inside trying to save the ladies. A nun had fallen and was helped by the Duchesse and was heard saying “Oh Madame, what a death” and the Duchesse responded, “Yes, but in a few minutes we will see God”. They were her last words.

Sophie-Charlotte en Bavière, Duchess d’Alencon was born on February 23, 1847. Her father Maximillian en Bavière & Duchesses Ludovica de Bavière of the House of Wittelsbach in Germany. On September 22, 1868, she married Ferdinand d’Orleans, Duke of Allençon the youngest son of the Duc de Nemours. Prior to the duke she was engaged to King Louis II of Bavaria in 1867 she discovered he was gay and postponed the wedding. When the war began in 1870 she and her husband and family moved to Paris to 32 Avenue de Frieldlane near the Arc du Triomphe.

After it was discovered she had a steamy affair with Edgar Hanfstaengl she was sent to a sanatorium in Austria to tackle her sexual desires. For 5 months she was left alone to become the lady she was supposed to be. She returned to Paris in January 1897 just a few months before her death.

Once the fire was controlled the grisly job of moving and identifying the victims began. The nearby Palis de l’Industrie off the Champs Elysees was used for the 126 bodies recovered, 118 of which were women. Another 250 were injured, many with disfiguring burns.

The Duchess d’Alencon was found burned in the arms of the Viscountess de Beauchamp. She was identified by the gold bridge in her mouth. Many families weren’t as lucky. A majority of the victims were burned beyond identification. Among the wealthy elite women mostly there were also six nuns. Six children between the ages of 4 and 10, and five men and many young girls not even 20 years old.

Other notable victims included Camille Moreau-Nelaton. Camille was an artist that began by taking drawing lessons from Auguste Bonheur, brother of Rosa. She went on to become a ceramic artist and painter and exhibited at the Salon numerous times between 1865 to 1881. In 1858 she married Adolphe Moreau-Nelaton, the son of the personal surgeon to Napoleon III. Adolphe was an avid collector of art and passed the love to their son, Etienne Moreau-Nelaton who had one of the most important collections in the Louvre and Orsay today.

Camille was attending with her daughter-in-law and wife of Etienne, Edmée Braun Moreau-Nelaton. Both women were killed in the fire. Etienne never married again and mourned his mother and wife for the rest of his life.

The Viscountess Bonneval, Marie du Quesne was able to escape the fire but ran back inside to save her friend but was overpowered by the flames and died. Her husband was able to identify her body by her jewelry.

Jeanne de Kergorlay, Countess de Saint-Périer helped other women escape through a high window until the floor collapsed below her and her instant death, but after she saved a dozen women including her niece.

Librarian Ellen Blonska was identified by her orthopedic corset under her layers of fabric.

On May 8, 1897, a national funeral was held in Notre Dame de Paris presided over by Cardinal François Richard de La Vergne. President Felix Faure was in attendance who had thought he lost his mistress Marguerite Steinhal in the fire but she ended up not attending that day.

Around Paris, the endless stream of funerals and processions to the many cemeteries were held in every corner of the city for a week.

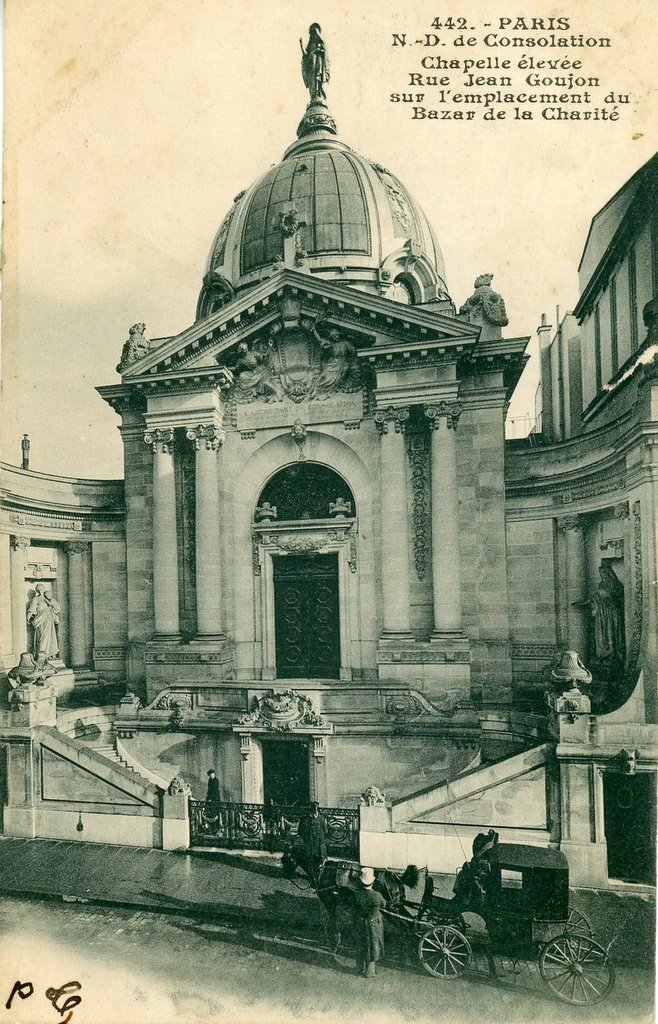

Days after the fire the Baron bought the property and gave it to the city with the intention of building a memorial for the victims. Cardinal Richard began a fund to erect a chapel at the sight and one year later on May 4, 1898, the first stone was laid and two years later on the same day in 1900, the Chapel of Atonement was inaugurated in memory of the victims. More than 86,000 items were pulled from the burned remains and added to the chapel, including a private space reserved for the family alone.

On February 28, 1899, the city of Paris also created a monument to the “unrecognized victims” in the 92nd division of Pere Lachaise.

The funeral for the Duchess d’Alençon was held in the Saint-Philippe du Roule church on the Rue de Faubourg Saint Honoré. Her coffin was taken to the Chapel Saint Louis in Dreux where members of the Orleans family are buried.

A lavish tomb in marble of the Duchess created by Louis-Ernest Barrias depicts her after her death laying next to burnt beams in full dress. A little too shocking to visitors it was moved to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dreux and replaced with a new tomb by Charles-Albert Walham in 1912. A few beams are still visible but the Duchess is now laid to rest clutching a cross.

In 2019 Netflix premiered an eight-episode series, The Bazaar of the Charity, The Bonfire of Destiny in the US featuring Audrey Fleurot. The characters are fictional but the event itself in the first episode is historically accurate.