This week is the 79th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris and the march to the end of World War II. In 2019 for the 75th it was celebrated with wonderful stories and remembrance, and unless it hits a big milestone year it is all but forgotten. I’ve never thought it was right that people only focus on the big anniversaries, these events and more importantly the people behind them should be remembered every year and every day.

If you want to really get an idea of the years of the Occupation, Resistance, and Liberation you must visit the Musée de la Libération de Paris, located in the Place Denfort-Rochereau near Frédéric Bartholdi’s Lion de Belfort and the entrance to the Catacombs. The new location opened on the 75th anniversary of the Liberation, August 25, 2019. The former museum was just past the Gare Montparnasse and somewhat hidden from visitors.

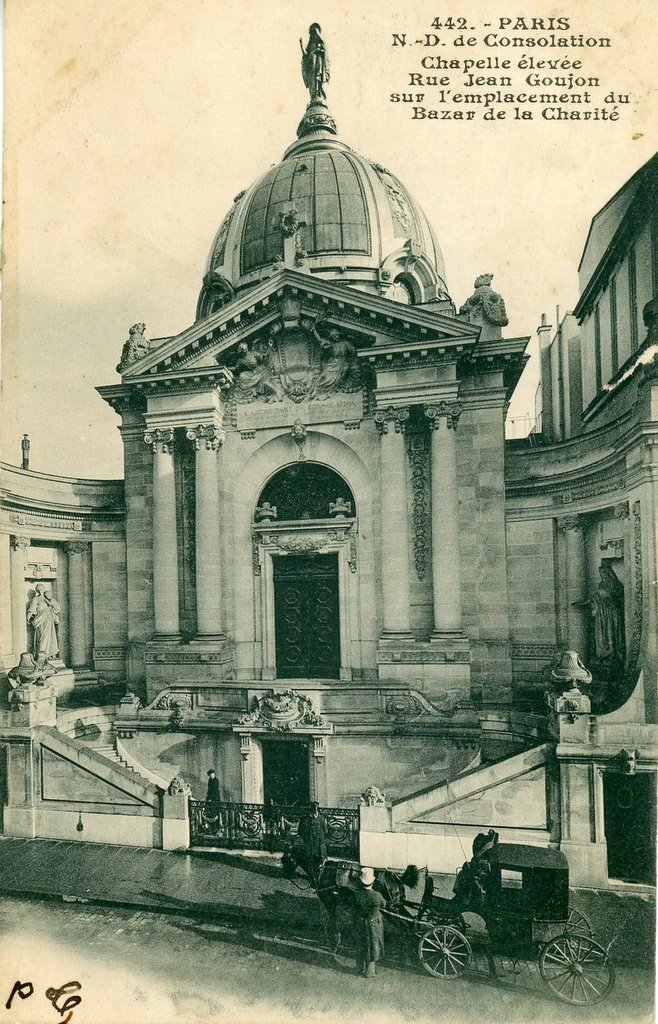

The original opened on August 24, 1994, for the 50th anniversary and also included the Musée Jean Moulin. In 2015 they decided to move it to a more visible location and their choice was perfect. The Pavillon Ledoux built in 1787 by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux was one of the fifty barriers surrounding Paris for the General Farmers to collect taxes on goods arriving in the city. The Neo-Classical building and its twin across the street housing the entrance to the Catacombs are two of the handful that remain. Ledoux also designed the rotunda pavilion at the beautiful Parc Monceau Today the pavilion is named after its designer but it was known as the barrière d’Enfer, barrier of hell.

Not only was the location chosen for the wonderful building but it also sits over the underground command base for Colonel Rol-Tanguy and near Jean Moulin’s former hideout on Rue Cassini. When the museum was moved to its current location it morphed three museums into one. The Musée du Général Leclerc and Musée Jean Moulin became a part of the museum we see today. Each man was an integral part of the Liberation of Paris and Rol-Tanguy can’t be forgotten either.

Jean Moulin was born on June 20, 1899, in Béziers in the south of France. Mobilized on April 17, 1918, he served in the Engineer Regiment of WWI. Joining late into the war, he didn’t fight on the front lines but he did see the devastation left behind to the small villages of the Vosges. After the war, he obtained his law degree and then served as chief of staff for the deputy of the Savoie. Until the start of WWII, he was the sub-prefect for towns all over France moving frequently.

In June 1940, as the Prefect of the Eure-et-Loir in Chartres he was arrested by the Germans for refusing to sign a declaration that a group of Senegalese men killed residents of La Taye. It was actually the Germans who had killed them. Standing by his principals he was beaten and tossed into jail where he tried to cut his own throat with a shard of glass. A guard intervene and stopped the bleeding, but the act would lead to his signature style being captured in a famous photograph taken of him to cover his scar. Taken after his release the photo of the dashing young man with a scarf around his neck, wool coat, and hat was taken by close friend Marcel Bernard in Montpellier.

Word of his brave actions reached Charles de Gaulle in London and he requested a meeting with Moulin. The two first met on October 24, 1941, when De Gaulle gave him the assignment in uniting the various groups of the Resistance.

On May 27, 1943, the first meeting of the Conseil National de la Résistance was held at 48 rue du Four. Less than a month later on June 21 in Caluire-et-Cuire near Lyon, a meeting at the home of Dr Frederic Dogujin was held. Seven leaders of the different factions of resistance groups were in attendance including Jean Moulin as well as René Hardy. Just as they sat down the Gestapo rushed in and arrested everyone in attendance, although Hardy was the only one not handcuffed and was quickly released.

Hardy had been arrested on June 10 and taken to Klaus Barbie in Lyon. There isn’t any recorded information on what happened at that meeting. After the war, he was accused and taken to trial twice in 1947 & 1950 and acquitted. At the 1987 trial of Barbie, he admitted his contact with Hardy and the info that led to the arrest of Moulin.

Upon the arrest of Moulin, he entered the Lyon prison of Montluc until the Nazis took him to Gestapo HQ and Klaus Barbie awaited his arrival and torture. On July 8, 1943, in the midst of a transfer by train to Berlin Moulin died at the Metz train station. There is some doubt about that being the location as it took 6 months to create a death certificate by the Germans.

He was returned to Paris where his ashes were interred in Père Lachaise until 1964 when he was moved to the Pantheon. In one of the most moving ceremonies in French history, André Malroux gave an unforgettable speech to the hero. Today the two men lay at rest in the same niche of the Pantheon.

Antoinette Sasse was a close friend of Jean Moulin and also worked with him decoding messages. In 1943 through her vast connections in the art world, she set up a gallery in Nice that would also serve as a front to distribute pamphlets. With Colette Pons, the Galerie Romanin at 22 Rue de France in Nice held exhibitions that included the art of Picasso, Renoir, Chabaud, Maurice Utrillo, and past podcast lady Suzanne Valadon. Through those years together she amassed many of his personal papers when she emptied his apartment when he needed to flee and with Moulin’s sister Laure she had more than 3,000 pieces that would become the basis of the museum today.

The museum begins in 1939 with the stories of what led up to the start of the war and the background on the lives of Leclerc and Moulin including personal items. Leclerc had a pension for drawing and his Lefranc pastels he owned in 1920 alongside his skis and boots give you a little glimpse into the man.

Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque was born November 22, 1902, in Belloy-Saint-Léonard and was destined for the service. In 1922 he enrolled in the Ecole Speciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr and finished 5th in his class in 1924. By 1931 he was an instructor at the same school. During WWII he was stationed in Belgium where he was arrested and later released. With his wife and 6 children, he was able to escape to London on July 24, 1940, where he met with De Gaulle.

De Gaulle saw an exceptional soldier and leader in Leclerc and in August he promoted him to Colonel and directed him to Cameroon where he served on behalf of the Free French forces. The Vichy government sentenced him to death for his actions in absentia and an arrest warrant was placed on his head.

Leclerc continued on through Morocco and returned to Paris in August 1944. It was Leclerc that signed the papers and took in General von Choltitz at the Gare Montparnasse and the next day was walking down the Champs Elysees next to Charles de Gaulle.

Continuing on after the war he liberated troops in Strasbourg. Led the first troop to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest and onto Algeria.

On November 28, 1947, the B-25 he was on crashed in a sandstorm, and he and the 14 passengers were never recovered.

On December 4, 1947, a National Funeral was held in Notre Dame followed by a procession to the Arc du Triomphe and ending at Les Invalides where the hero is buried today.

The museum covers both these great men as well as the hundreds of other stories throughout World War II.

Chronologically charting the march of the war from the start to the Liberation is heartbreaking. Alongside propaganda posters of the Vichy government, photos of how the Germans covered Paris in their Nazi flags, and items left behind by families all give you a very visceral and emotional reaction that is hard to contain. The small shoes that once belonged to a child that was taken with his family to Auschwitz are hard to digest.

In one case a tile that was once in the La Muette housing in Drancy where many Jewish families were taken before being sent to Auschwitz still shows the faint markings of the Sétion family. Ida Sétion and her four daughters Jacqueline, Elie, Eliane, and Monique were arrested on November 4, 1942, deported on November 9, and killed on November 14. Before they left she inscribed on the tile “Famille Sétion du 8/11/42 au 9/11/42….Destination…..” The fear they had to be going through is heartbreaking and doing all she could to keep her four daughters safe and calm must have been horrific.

The museum brings to light many names you may never have heard about and their stories of bravery few can even imagine today. As you near the end of the museum you start to hear recordings of joyous celebrations, all ending with the Liberation of Paris. Images set to music and the cheers of happy Parisians filling the Champs Elysees and Hotel de Ville in celebration are bound to make you smile.

One of my favorite things in the museum is a dress made for the Liberation of Paris by Marguerite Sabut and her mother. At the start of August, they began to make the dress hoping she would soon have a reason to wear it. The dress includes paper cutouts of the Eiffel Tower, Arc du Triomphe, Bastille Column, and other landmarks in Paris. She also had a small purse made with the Cross of Lorraine as a clasp and roosters on it. Seventy-nine years ago on August 26, 1944, she finally had her chance to wear the dress during the parade on the Champs-Elysées as she watched General De Gaulle walk by. A few lucky soldiers signed her bag as the perfect reminder of the day.

I hope I have convinced you to pay a visit to this lovely museum. Special exhibits are also planned throughout the year and with only a fraction of what they have on display it pays to go a few times to see it. The museum itself is free to the public, but a reservation and a small ticket fee are required to visit Colonel Rol-Tanguy’s former headquarters where he along with his wife Cecile worked to save Paris and France.

4 Avenue du Colonel Henri-Roy-Tanguy 14e

Tuesday-Sunday 10 - 18